The Earliest Example of Evangelical Christian Lobbying for Justice in America

The Brainerd Missionaries and the Tragic Lead-up to the Cherokee Removal

On September 16, 1813, Dr. Timothy Dwight, then president of Yale College, delivered a sermon before the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). His words expressed a vision resonant with the evangelical zeal of the Second Great Awakening: he believed the Gospel was destined to be preached globally and that people across all continents would embrace Christianity. Dwight’s sermon encapsulates the ambition and certainty of northeastern evangelicals, who saw all “heathen” peoples—far and near—as fitting recipients of the Gospel’s transformative power. This enthusiasm, however, was not without a heavy cultural bias, laced with the superiority of European civilization over Indigenous cultures.

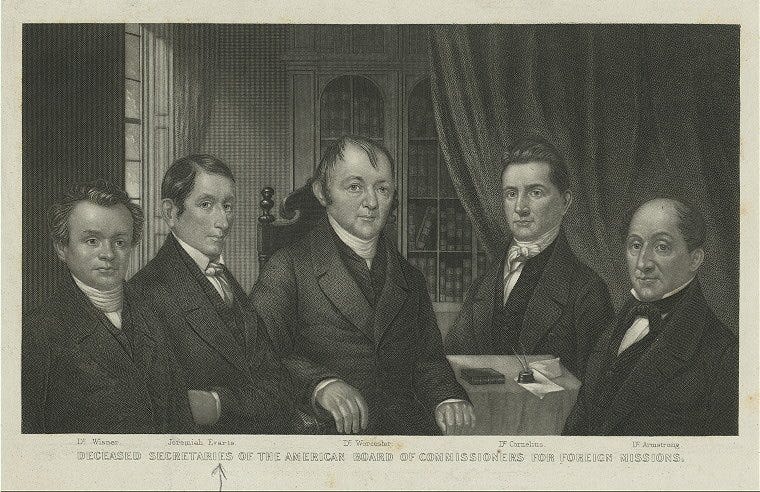

The ABCFM, founded in 1810 primarily by Congregationalists from Massachusetts and Connecticut, soon saw involvement from Presbyterians and Dutch Reformed Calvinists, giving it a broad denominational backing. This ecumenical spirit was aimed at advancing the Gospel’s reach, though ABCFM remained focused on a more narrowly defined religious mission compared to contemporaries like the American Bible Society. Early plans focused on distant lands, such as India, but practical obstacles—including opposition from British colonial authorities—redirected their attention closer to home: to the Indigenous tribes of the American Southeast.

By 1816, the ABCFM was actively planning missions among the southeastern tribes, particularly the Cherokee and Creek nations. This decision wasn’t purely spiritual; it was also political, shaped by America’s expanding frontier and the national aspiration to “civilize” Indigenous people as a means to facilitate westward settlement. With backing from the U.S. government, which saw these missions as aligning with its own agenda, ABCFM representatives, including Rev. Cyrus Kingsbury, found a sympathetic ally in Washington. The Monroe administration, following the War of 1812, perceived Christian missions among the Indigenous as a solution to reducing conflict as settlers moved westward. Civilizing the “southeastern tribes” thus became intertwined with American expansionism, as missionary and political goals became two sides of the same coin.

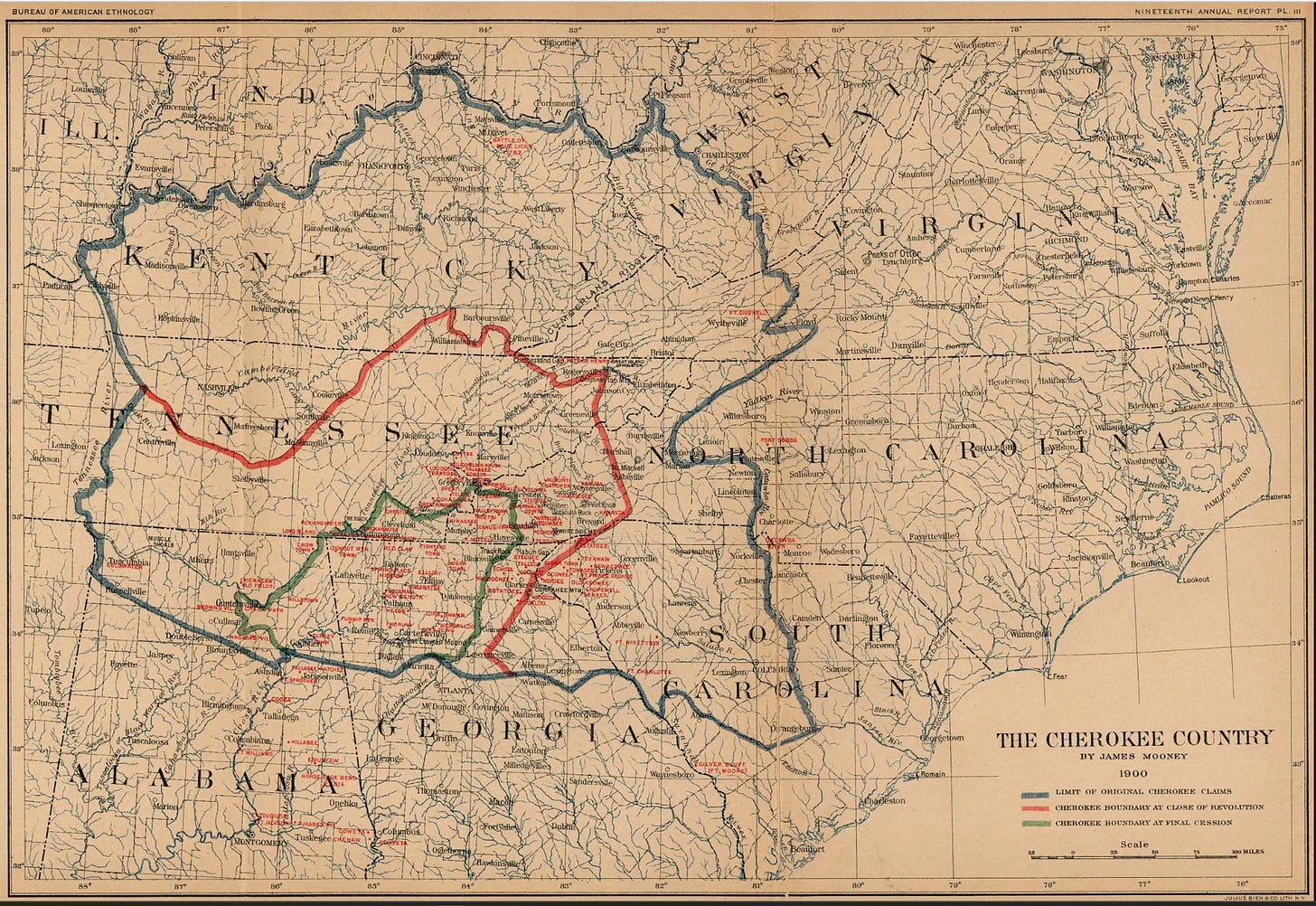

The Brainerd Mission, named after the revered missionary David Brainerd, was established in Chickamauga (present-day Chattanooga) and became a model of the evangelical missionary approach. There, students were taught vocational skills like farming and smithing, and were given English language instruction, often with an undertone of erasing Indigenous culture. These missions, though often grounded in good intentions, operated under a paternalistic framework aimed at assimilating Native students into Euro-American customs and values. Yet, the Cherokee people were no passive participants. Their response was informed by centuries of trade and diplomatic relationships with Europeans, which had resulted in Cherokee leaders of mixed heritage. This cultural hybridity helped forge some common ground with missionaries like Kingsbury, who saw their work as creating Christian “citizens” of the Cherokee youth.

Nevertheless, cultural tensions soon surfaced. Cherokee parents voiced objections to certain aspects of the missionary program, especially corporal punishment and agricultural labor for boys—both foreign to traditional Cherokee culture. Converts within the Brainerd community struggled to discern which Cherokee customs were permissible and which the missionaries deemed incompatible with Christianity. For instance, missionaries wrestled with practices like polygamy, unsure how to navigate such complexities. While Rev. Ard Hoyt believed a Cherokee man with three wives was sincere in his faith, the ABCFM prudential committee insisted he separate from all but one—a requirement that Hoyt found practically impossible to enforce. This level of consideration for cultural nuance demonstrated the missionaries’ emerging sense of advocacy and connection with their Cherokee brethren.

The relationship between the missionaries and the Cherokee evolved within a shifting political landscape, marked by mounting settler pressure on Cherokee lands. Initially, U.S. government policy, supported by Christian reformers, aimed for Indigenous assimilation through peaceful coexistence. Yet, the political tide shifted dramatically with the rise of Andrew Jackson. By the 1820s, Jackson’s influence steered national policy toward forced removal, culminating in the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Jackson, a man of the frontier, held little sympathy for the Cherokee Nation, despite their efforts to adopt European ways, which included the establishment of a democratic government and constitution modeled on the United States.

Amid this charged atmosphere, missionaries like Samuel Worcester and Rev. Daniel Butrick emerged as staunch defenders of the Cherokee. They helped amplify Cherokee voices through the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, edited by mission-educated Elias Boudinot, which published in both English and Cherokee. Through the Phoenix and other avenues, the Cherokee presented a nuanced critique of American expansionism. They questioned the inherent inconsistency in a government that preached democracy and justice yet undermined the rights of Indigenous nations. Chief John Ross, a steadfast advocate for his people, appealed to the Supreme Court, culminating in the landmark case Worcester v. Georgia, which upheld Cherokee sovereignty. Yet, Jackson refused to enforce the decision, famously stating that Chief Justice Marshall should be the one to enforce it.

The missionaries themselves struggled with the political and moral implications of forced removal. As the government persisted, some missionaries, including Worcester, advocated reluctantly for Cherokee relocation, reasoning that it might be safer than resisting the inevitable. However, Chief Ross and the vast majority of the Cherokee held firm against relocation, leading to the tragic signing of the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 by a small faction without official Cherokee government endorsement. The treaty ceded Cherokee lands and triggered the forced removal known as the Trail of Tears. The signing, and subsequent removal, underscored the profound failure of the American government to honor its commitments to Indigenous nations, despite the Cherokees’ remarkable adaptation to American social and religious structures.

The removal was brutal. The conditions of forced marches, malnourishment, and the abuse the Cherokee suffered on the Trail of Tears devastated the nation. Missionaries like Butrick, who accompanied them, bore witness to their suffering with a profound sense of disillusionment. Butrick’s journals reveal the deep inner conflict of a man who once believed in the American promise but now saw it as complicit in a grievous injustice. His reflections cut through the veneer of manifest destiny, condemning the moral hypocrisy of a nation that preached freedom but practiced exploitation.

The Brainerd Mission, initially founded to spread Christianity, became emblematic of the conflicting ideologies at play in American society. The missionaries who remained with the Cherokee saw their mission transform from one of simple conversion to one of advocacy. Figures like Worcester and Butrick grew disillusioned with the U.S. government’s treatment of the Cherokee, ultimately questioning the fundamental contradictions in American society. In 1838, the ABCFM prudential committee finally concluded that continued efforts among the southeastern tribes were futile, a grim acknowledgment of the mission’s dashed hopes.

The Cherokee response to these events reveals their resilience and capacity for adaptation. Despite the missionary agenda’s limitations and the U.S. government’s betrayals, Cherokee converts maintained their faith, embodying the spiritual resilience that missionaries like Butrick had once sought to instill. The tragedy of the Trail of Tears did not obliterate Cherokee culture or faith; instead, it highlighted the Cherokee’s steadfastness and moral clarity, even as they suffered under an unjust system. The missionaries who accompanied them, and who bore witness to their endurance, were themselves irrevocably changed, grappling with their complicity and the limitations of American evangelicalism.

In the final assessment, the American missionary endeavor in the southeast failed to protect the Cherokee from removal, yet it left an indelible mark on both the missionaries and the Cherokee themselves. The evangelical witness provided by figures like Evarts, Worcester, and Butrick underscored the contradictions in America’s identity and foreshadowed later religious critiques of government actions. This legacy of advocacy, emerging from the complex relationship between missionaries and Indigenous communities, remains a testament to those who dared to challenge their society’s norms and stand for justice, even when their own institutions faltered.